A Beginners Guide to Home Studios: Part 2

- outreach635

- 6 hours ago

- 21 min read

Interfaces & Microphones

Written and Edited by: Saige E. Davidson, MOSMA Outreach Coordinator, 2023 Alumni

Published: Feb. 6th 2026

Now that you have your computer and your headphones, how on earth do you actually record sound into the DAW on your computer?

Well, the next thing you’ll need is an interface. I like to call this piece the beating heart of Audio Production, because its function in the chain reminds me a lot of what your heart does when it beats.

The main job of an interface is to convert the analogue signal coming from an instrument or mic cable, into a digital signal that your computer can understand. The interfaces second job is to do the reverse process, and convert the digital signal back into an analogue signal, so that you may playback the audio through headphones and/or monitor speakers. We call the former an A/D converter (analogue to digital converter) and the ladder a D/A converter (Digital to analogue converter).

They also have a third job, and that is to provide amplification to the signal so it may reach the DAW at your desired level. This is done by what we call a pre-amp, or pre-amplifier. When you turn up the gain on your microphone, this is the device you are engaging. Its job is to amplify the input signal to your desired level. In a studio, these are commonly separate units that we mount on racks.

One may wonder why you can’t just use a USB microphone to get the sound into your computer. The answer is that you can, but at your own risk.

I speak as someone who has owned one of the better USB microphones: It is a pain to keep it under control, and the audio quality I did get was not worth the amount of effort I put into it.

A microphone is inherently an analogue device. Yes they do have circuitry and wires, but the signal they output is analogue. This means that without something to convert it into a digital signal —which is just binary data— we have no way of recording it into anything other than other analogue devices such as tape recorders. In a typical modern recording scenario, this is where your interface or mixer would come in, because these devices, as previously stated, convert that signal as their main job.

You also have to consider the fact that microphones need a pre-amp to function. Sometimes they are analogue. Sometimes they are digital. I don’t wish to go too deep down that rabbit hole right now. The important thing is that you have all these pieces —the microphone, pre-amp, and A/D converter. In a USB Microphone, that all has been condensed into just one component; and at this point in time (I don’t know if this will be the case forever) that causes more problems than good, and a lot of that has to do with the cost of these individual components. Typically cheap parts sound cheap because they are low quality.

In addition to this, the USB cable is also a problem,

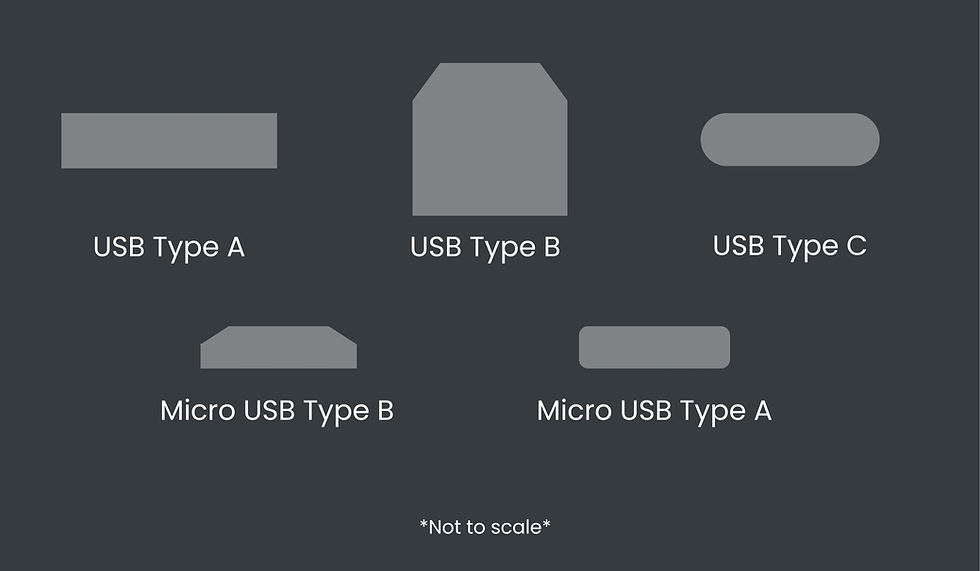

and it isn’t that USB cables are necessarily bad at carrying audio. They do it just fine when we use SSD's (Solid State Drives). It’s all just binary data at that point, so as long as the cable is decent, then it shouldn’t cause issues in that sense. However, it does become a problem when you consider that a condenser microphone —what these USB microphones tend to be— needs 48v (48 volts. This is also called phantom power), to actually run properly. A standard USB type A cable can only carry up to 5v, and a standard USB type C cable, while significantly better, will usually max out at 20v. You will get audio from it, but you won’t have the headroom you need; Headroom being the buffer between the volume of the signal in decibels, and the point where the signal starts to distort.

I don’t believe it will stay this way forever. The USB PD 3.1 was released in 2021 and would theoretically be capable of powering a condenser microphone. Unfortunately, I cannot find evidence of any USB microphones actually using it yet, and that also doesn’t solve any other problem these microphones have.

This leads me into one more issue with these microphones. Even if we upgrade the parts, and we get the correct cable, you still have to power this thing from your computer power supply, that is already allocating power to everything from your GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) and computer fans, to your keyboard and mouse. It will only allocate so much power to that USB input.

If your computer is trying to power several extra things, or if there is insufficient power to anything more important than that USB port (many components will fall under this), your computer is going to redirect that power so that the more important things, allocating even less power to the USB port the microphone is plugged into. So there is a high likelihood that you are going to run into problems with your audio due to the instability of your power supply.

So, to sum it up, USB microphones are cheaply made, underpowered (lacking the appropriate headroom), and unstable.

They work as gaming microphones, or for online video calls, but otherwise their sound generally lands in the range of ‘kind of okay’ to ‘almost entirely unusable’. Even if you consider potential usage in SFX —the audio equivalent of downgrading a t shirt to pajamas. I say that enduringly— you still have to worry about the signal suddenly dropping out, leaving you with potentially huge gaps in what you actually intended to capture.

To be clear, I am certainly not saying it’s impossible to use, but imagine you think you just got the perfect take, but when you play it back, it’s become distorted, or there are sections of audio missing. That is why, as our technology currently stands, I urge you to avoid them if you can. Interfaces, allow for reliable, high-quality recordings and high-quality playback, while still maintaining a fairly condensed set up (See figure 1). They also provide you with a far superior headphone jack that is post DAW. This means that if you add effects processing like reverb, compression, overdrive, and so on, you can hear them clearly without needing a ridiculously long cable to do so, or battling with lower quality headphone jacks designed for just general listening rather than a more professional level of audio production.

Much like headphones, you’ll need to know a few things before you decide on an interface.

How many inputs will be needed?

This question can also be worded as “How many instruments do I want to record at once?”. What I mean by this, is that for every sound (signal) you want to record at a time, you need at least one microphone. And for each microphone, you need one input. For example, if you are looking to record a full drum kit, you’re going to need far more inputs then if you are just recording guitar and vocals.

For that full drum kit, I recommend at least four microphone (XLR) inputs. While it is absolutely possible to do it with just two well placed overhead microphones —and many amazing drum recordings have been created that way. Led Zeppelin’s “Where the Levee Breaks” or many Brendan O’Brian recordings for example— that is something that would come with a lot of practice, experience, and a knowledge of stereo recording. Absolutely try it if you would like a good challenge, however it isn’t the most beginner friendly method.

Guitar and vocals are typically much simpler to record.

If you have an Acoustic guitar, and you like to sing and play at the same time, you’ll want to have two XLR inputs, otherwise you’ll be stuck recording each instrument separately.

If you’re an electric player, you can plug your guitar rig, minus the amp, directly into the interface using the Line level input (TS input. See Figure 3); which will look identical to the input jack on your guitar amp. Be sure that you haven’t plugged into the headphone output (I still do this sometimes). If you feel like this is missing the sound of the amp and you’re not sure how to fix that, there are both pedals and plugins that ‘model’ amps, and make it sound as if you are in fact playing through one. If you have a digital board, there should be an amp modeller built in for this exact reason.

You can also record your guitar amp/cabinet with a microphone, in which case, I do recommend you record your vocals and guitar separately to prevent yourself from catching the guitar amp in the vocal recording, or vice versa. This means you would only need the one microphone input, maybe two if you would like a second mic on your guitar, which is an incredibly common practice.

You’ll likely run into some inputs that are a combo of mic (microphone/XLR) and Line (Instrument cable) inputs. They’re, rather literally, called them Mic/Line inputs. Sometimes these are very handy, particularly if you are someone who likes to record several different types of instruments separately. In that case, they provide some flexibility. Other times they feel more like a gimmick for sales people to make you feel like you have more inputs, when in reality, you have half as many as you would if those inputs were not combined. That's why it's so important to establish what you actually need.

Do I want something that can be expanded on later?

When you expand an interface, you are adding more inputs to your set up. Some interfaces have this capacity, some do not. It depends if they have S/PDIF (Sony/Philips Digital Interface Format) or ADAT (Alesis Digital Audio Tape) (Figure 2) connectivity or not. I have seen some that actually do this through thunderbolt, but most brands will use the former connection types. If you’re not sure if you want to or not, and you’re just recording guitar and vocals, then you’re probably going to be just fine without this feature. People who aspire to record entire bands at once may want to eventually invest in something that can do this, or they may just want to look towards something like an 8, 12, or 16 channel mixers, depending on tastes and their workflow.

This feature is something you generally see more in the studios of professional engineers or hardcore hobbyists, and that is simply because it can be very very expensive. It’s more common for people to choose to work up to this point, rather than start here. The only reason I even mention this is because I used to sell these for a living, and this was a common selling point I frequently overheard, and also had used on me. Personally, I don’t need this particular feature right now, and I likely won’t even consider it for a very long time, because the size of recording that would justify this is something I would prefer rent out a studio space for.

Am I using PC or Mac?

Not all brands do this, but some interfaces will have two different versions. One for PC and one for Mac. This can be for multiple reasons, the actual connection from the interface to computer being one. It can also be due to software compatibility, as interfaces will often come with bundles of software when you buy them new, including the software that is required for it to function properly.

It never hurts to double check if you aren’t sure. It will save you the trouble of having to swap for the correct interface. Or if you have bought it second hand from somewhere that doesn’t have a good return policy, it will save you money and frustration.

Is a built-in compressor something I’d like to have?

This is definitely one of the ‘bells and whistles’ that you can get in an interface. For those who don’t know what a compressor is, it is a tool used for dynamic control of audio. This is a bit of an oversimplification but in essence, it squishes loud audio down and pulls quieter audio up, with a goal of making it sound more even overall; without losing all of the dynamic change.

It can be nice to have if you’re someone who likes gaming and is chatting with friends online. It is also nice to have for recording vocals or acoustic guitar, as it will allow you more dynamic control without having to necessarily limit how loud or soft you actually are.

And that's the thing, it’s just nice to have. Nice enough that it is also a very good sales pitch —one I’ve used many times myself. It’s just not necessary for most people; and it really is a question of how you want to structure your workflow rather than it being something you absolutely need in your set up. Most beginners don’t even know what kind of workflow works best for them yet, and compressors are one of the more difficult tools to learn, so this addition has the potential to cause unnecessary confusion for people just starting out. Besides, there are other ways you can compress your signal (sound) coming in, such as simply using a digital compressor on your computer.

It sounds more complicated, but it is quite simple, and most DAW’s come with compression plugins so you probably won’t even have to go out of your way to purchase and download one.

There are also plenty of free plugins available that will serve you well. Klanghelm makes a couple, as does Analog Obsession, and a number of other brands. Of course you should make sure you’re downloading from a reputable source, like anything on the internet. I like to check places like Reddit and Gearspace —even YouTube sometimes— to see what actual audio people have to say before downloading. This also assists in managing the consumption of my computer memory (RAM).

Here is a website that contains a list of free plugins to get you started on your journey:

I've used several plugins on this list myself, and I've encountered these brands many times before. The website may look a bit sketchy if you're unfamiliar with it, but it's just a place where various programmers share what they have been working on and trade information such as good free audio plugins.

Is having a MIDI connection important to me?

Some interfaces have MIDI IN and OUT connection (they will not have a thru connection because that would not work). If you’re a huge synthesizer fan, or you have a band member who is one, then this may be something you would like to consider.

For anyone else, this is not a necessity. It is also very easy to pop into a music store and grab a USB to MIDI conversion cable, should you happen to need it for a project. It shouldn’t have any significant impact on the fidelity of the recording —if that is a concern of yours— and it leaves space on the interface to have more inputs.

For those who would like to look at second hand options, a good website to start with is Reverb. They are a reputable website for second hand music gear of all shapes and sizes, and their condition rating system tends to be quite accurate.

Here in Canada you can also of course look at Long and McQuade. Their Gear Hunter page can have some fantastic stuff. Of course, it is important to pay attention to what you’re buying and ensure that the model number and condition are accurate. I can tell you from working there that sometimes (not often) they aren’t correct, and that can be caused by a number of things such as their systems being quite old and a bit clunky in some ways. That includes the process for adding items onto Gear Hunter.

They do have a good return policy, and they also will allow you to trade in gear such as guitars, keyboards, monitor speakers, and so on, to put towards a purchase. It is very common for people to “Trade up” there, meaning they will use their old guitar —or their many old guitars— to put towards buying a guitar that is worth more than the guitar(s) they had. This isn’t as common with interfaces, but I have seen people do it. Monitor speakers as well. I am unsure of their policy with other audio gear, as it does depend on if they feel they can sell or rent what you wish to trade in.

If you see a piece of gear marked as ‘Demo’, what that usually means is that there will some minor damage to the surface, or it has been opened and used for display for a long time, however it is otherwise a functioning piece. While I’m not 100% certain of any other company, but in the case of Long & McQuade, it also means someone just didn’t want it, ended up returning it and had already tossed out the box or knicked the finish.

Here are a few more websites that offer second hand gear:

I will note that most second-hand websites for music gear that we here in Canada have access to, at least sites that I am familiar with, are US based. If you are comparing a product in Canada to one in the US, make sure you calculate the shipping to get your final cost. It is common for music gear to appear to be cheaper to get in the US, but often you will actually pay more.

Facebook marketplace and Kijiji can be good, but that is dependent on your area and the people within it. It can also be difficult to test something like an audio interface during one of these sales. Especially if you don’t have a laptop, and you don’t necessarily want a stranger coming into your house just so you can maybe get a good deal. At least with these companies, they generally try to test everything, and if they don’t and it’s broken, you’ll be able to get your money back.

But how do I capture the signal?

Now you have your computer, your headphones, and your interface. The next thing in the chain I’d like to tell you about is microphones.

This one can be a bit difficult to choose, and understandably so. There is such a range of products, prices, and opinions. I would argue even more so than headphones. My advice is if you would like to be picky, like I myself so often am, then find somewhere you can rent some microphone options out.

You can make recordings of each mic, and then compare them directly. Just be sure that you eliminate all other variables, meaning be sure that every microphone is recording the same signal, in the same spot, in the same room, preferably with the diaphragm (see Figure 4) of the microphone at the same or a similar angle (This is also a good ear training exercise). I know of engineers though, who will just record with a very basic microphone, get a pretty good recording, and then just EQ (Short for Equalizer) it into what they want it to be prior to doing the full mix.

It really depends on how much work you’d like to do in the mix. When you are choosing a microphone, some things to ask yourself are:

What am I recording?

You aren’t typically going to use for an electric guitar amp what you would use for a soft voice. Not that you can’t. And if you only have a limited number of microphones then working with what you have is very normal for Audio Engineers at all levels. But if you are able to have different microphones for both, then it will likely save you a lot of work in the mix.

The point of getting a good recording is to make the rest of the process go by with ease.

Is the signal loud, or quiet?

For louder signals, you may want to choose a dynamic mic as they are electromagnetic, which causes them to simply be less sensitive to sound coming. Another option may be a condenser with a pad switch, which is an extraordinarily handy little switch that makes the microphone take in less signal so the loudness of said signal doesn’t cause the microphone to clip (clipping is when the signal becomes too loud and starts to distort the recording).

For more moderate or quieter signals, you will want to go for a condenser, as they are more sensitive by nature of them using electrostatic electricity, and can be gained up to pick up even the quiet rustle of your clothing. Condensers, as I previously stated, need 48v of power (Phantom power) to work as they should.

When they record foley (anything an actor touches that makes a noise) and location sound for film (on set dialogue, sometimes Background tracks or other background sfx), what they use is called a shotgun condenser microphone, which means it is a very directional (focused) condenser. It actually looks like just a long tube, with many slots. It's very cool. Sound on Sound did a fantastic article explaining how they work.

Does the source of the sound, sound more dark or bright?

Bright: High, Sharper, cutting, ringy, shimmery, Clean, Focused, etc.

Dark: Low, Mellow, Warm, Smooth, Complex, etc.

Cymbals are probably the easiest to hear this in, but this applies to all instruments, and also to microphones, headphones, speakers, the room you are working in. It is a quality of sound and also a quality given to sound by what it interacts with. Say you have a very bright cymbal, and it is just a bit too much for the song, but it’s all you have, and you don’t want to create a bunch of work for yourself when you go to mix. This isn’t an uncommon scenario for most of us in the recording world.

What I would do is I would use a microphone with a bit of a darker sounding response to tone down that brightness at least bit, and vice versa if the cymbal is too dark. You can also utilize this to bring out more of the brightness or darkness in an instruments sound, simply by choosing a microphone with a response that is similar to, or more pronounced than, the character of the instrument.

There are other things you will want to consider too; such as rejection, which refers to the microphones ability to reject (not pick up) sound that it isn’t pointed at.

For the most part, unless you are playing an acoustic guitar and singing at the same time, it’s not something you have to worry about too much. It is common, in these cases, for the sound of the guitar to ‘leak’ a bit into the vocal mic, or the vocals into the guitar mic. This has the potential to cause difficulties in later steps in the music production process, and often leads to frustration if you lack the tools and/or knowledge to fix it.

If you are recording drums, then this leakage, as we call it in the audio world, is something you will likely run into when your mic up your snare and hi-hat. You will also likely run into it on other pieces of the kit as well. While we try to use the rejection of microphones to minimize this leakage as much as possible, drums are pretty darn loud, so we do what we can to eliminate as much as possible.

That being said, be wary of taking out too much when it comes to instruments like the drums, as you will lose the feeling of real drums if your drum microphones have become too isolated. We expect drums to be big and loud and to hear the cymbals and snare in the tom microphone a bit, we just don’t want so much leakage that the intended signal is drowned out.

You can improve the leakage of sound in the first example by positioning the vocal mic up towards the vocalist’s mouth, alas, aside from recording the vocals separately there isn’t much of a way to eliminate that leakage entirely. And that is okay. Part of the process is learning how to solve issues that may be caused because of this. To save yourself some grief while editing, ensure that you get a couple good takes, as you may have to edit the vocal and guitar track as if they are a single track.

The issue with the snare is just as simple. There are countless dynamic microphones at varying price points that have good rejection. Again, you may still have a small amount of leakage. That is normal. There are, of course, microphones out there that are so directional that there is barely any leakage, however you are looking at a much more high-end product, and therefore a high-end price tag. With those you also run the risk of being too directional. It's a bit of a balancing act.

When it comes to choosing a microphone for vocals, the first thing I tend to consider is the character of the voice. The second is the style of vocals.

In my experience as a vocalist, I have sung through many microphones that make my voice sound a bit dead, and before I understood why and how, I just assumed that this was just how it was.

I am a soprano two or mezzo-soprano, the second highest voice type, and that is a great thing to know when picking a microphone, because how high or low a voice sounds is a part of that voices character. If this is all I have been told by the musician, I would likely pick a sparkly sounding condenser microphone. The reasoning behind that is pretty simple. Condensers tend to sound a bit better on voices in general, and I would choose a sparkly sounding microphone because that particular quality tends to compliment my voice type quite well. People tend to use words like rich, or haunting to describe the tone of my voice. Those qualities are excellent, however I appreciate that a brighter microphone can make my voice sound more balanced.

It should be noted that by virtue of being a Audio Engineer, what I look for in my own sound sometimes is vastly different to someone who is just a vocalist. Microphone choice should be a topic you discuss with them so you can understand what exactly they are looking for. Their voice is their instrument, and a musicians instrument is extraordinary personal to them.

I have a friend who is a bass one, the second lowest voice type, and while I would still pick a condenser for him, I would likely reach for something maybe a bit more neutral. Yes, the sparkly microphone would likely sound good on him still, but sometimes on lower voices in particular I find that sparkle sounds almost unnatural, so it seems far more advantageous to pull out something a bit more well-rounded as it is more likely to be the complimentary mic I tend to look for.

This same unnatural feel can become apparent in some alto and alto two voices as well. It depends on how much sparkle is already in the voice. Some altos have this absolutely beautiful smoky, velvety voice (Cher being a famous example, who uses transparent, balanced microphones), and as a recording engineer, it is that voice you’re trying to capture. A bright mic could potentially destroy some of that, and for the most part, we don’t really want that.

A very crystal clear, bright soprano is also going to be different. If you put a bright mic on this person, they will most likely start to sound shrill in the recording. Like the bass voice, I would pull out a more neutral(transparent) microphone, maybe even one with a darker sound to round out the brightness of the very clear soprano voice. I’d likely try and set up both microphones and test both to see what the musician prefers.

You will l also run into different vocal styles at some point in your journey. Maybe you already have. Various Hardcore and metal —even some punk vocals—demand a microphone that can handle a lot of noise. As you may have guessed, dynamic microphones are wonderful for these instances. And because of the nature of these vocal styles, they usually sound pretty great on most dynamic microphones.

Soft, breathy vocals are always fun to record. You’ll have to use a condenser for them, as a dynamic most likely won’t be able to pick up the signal well enough. You will also have to turn your gain way up, which means you may have to be aware of your every movement, as there is a high chance the microphone will pick it up. You ideally want an isolated booth for this particular style, but closets filled with plenty of clothes and/or books are also an option.

Rap is focused towards spoken word and rhythm. In this context, I would want something that can really make the speaking voice shine. While this could mean the same microphone as the very first example, it could also mean looking at microphones made for broadcasting and podcasts. It depends on the character of the voice.

If you’d like to learn a bit more about different vocal characteristics, then here is a wonderful article from The National Centre for Voice and Speech , and another article explaining some vocal basics!

Be aware that not all vocal characteristics are relevant to your microphone choice, and may be affected more by your microphone placement (enunciation, for example), or it should be left alone all together. Something like vocal gravel or rasp occurs naturally in many voices and for the most part, is just a unique quality of the vocalist.

When you get your microphone, I also recommend getting your hands on a pop filter. As long as it can be comfortably positioned between the microphone and the mouth of the musician, it will work for your purposes. Some will clip onto the stand, and some will need a separate stand. The clip-on pop filter can be a bit finicky sometimes, but there is nothing that would actually stop me from using it.

You will also want to grab microphone stands. I recommend having at least one per microphone. The type of stand you will need depends on the application. Short, Straight, Boom, and Telescopic Boom are the four you will see most commonly. There are other variations, however microphone stands roughly follow the same blueprint. The Short Boom stand would be an example of a common variation. They are incredibly useful for drum kits, and nice to have when recording guitar amplifiers.

The Stort Straight stand comes in handy anytime you need to record someone speaking or singing while they are at a desk. Sometimes this is exactly how I will record my own vocals. They’re also handy for your talk back mic (the unrecorded microphone we use to speak to the musician in the booth. They can’t hear the sound tech otherwise. The musician will often have one in the booth with them as well), and can have their uses for drum kits and guitar amps. Their lack of articulation limits how much they can be used for, and that is where the Short Boom stand steps in.

The Straight Stand, is useful for things like musician talk back microphones, room microphones, a threaded pop filter, and in some cases for vocals or spoken word.

The Boom Stand, due to its articulation, is useful for most things. The only real downside is that its upper arm can get in the way of walking paths and will occasionally get hit. That is why we have The Telescopic Boom Stand. The shorter arm makes it easier to maintain a clear path and your microphone placement, however the standard boom stand will be a better choice if you need to record drum overheads, as they have more range in their height, and depending on the drummer and their kit, you may need all the height you can get.

While I won’t be covering microphone placement very much in this particular article , I will touch on it in part 3. I intend to cover that particular topic in far more depth , so stay tuned and feel free to reach out with any questions!

Next part coming in March!